How Buckhorn mine opponent adapted to activist’s life

*How Buckhorn mine opponent adapted to activist’s life*http://seattle.bizjournals.com/seattle/stories/2008/12/29/focus4.html?q=BUCKHORN%20KINROSS

by Greg Lamm, Staff Writer

When Dave Kliegman launched his quest to block an open-pit gold mine on top of Buckhorn Mountain, his daughter was 10 years old.

Today, Sarah Kliegman is a year away from earning a Ph.D. in organic chemistry, and her father is still a passionate advocate for the Okanogan County wilderness area.

“I knew it was going to be a big battle,” said Dave Kliegman. “I really didn’t have any idea where it would end.”

Kliegman formed the Okanogan Highlands Alliance in 1992. He later quit his job as a physical and occupational therapist working with handicapped children to work full time on battling the open-pit mine. Along the way, he unraveled the hodgepodge of state regulations related to mining, became an expert on century-old federal mining law and also banded together with other grassroots organizations fighting mines in the West, including on Indian reservations.

Kliegman, who carves wood sculptures as a hobby and also manages a 120-acre woodlot, said soon after hearing about plans to launch the open-pit mine, he went to the site. He was appalled that the U.S. Forest Service was allowing exploratory drilling every 50 feet on the whole mountain, and also allowing the construction of 33 miles of what he called roads, but the Forest Service called interconnected “drill pads.”

“That’s when I realized that this was not going to have much integrity and if I wanted to do something about it, I had to get involved,” he said.

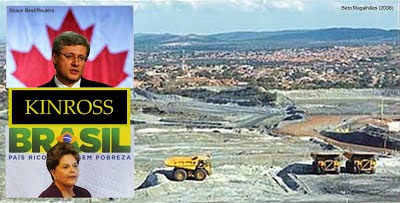

Several years ago, Kliegman’s group was able to block the open pit. And earlier this year, Kliegman’s group and other advocates struck a deal with current mine owner Kinross Gold Corp. that ended the last legal challenge to mining operations that will now be underground. The deal includes more environmental protections and more than $1 million to monitor groundwater near the mine.

Kliegman said the group’s biggest success was stopping the open-pit mine, which he said would have had a disastrous environmental impact on the area. It would have meant 100 acres of toxic water sitting on top of the mountain, which feeds five creeks. Kliegman said he is proud of his group’s efforts, even though he would rather not see any mining at all on Buckhorn Mountain.

“I’m glad we were able to make a difference,” he said. “I think it’s a relatively positive outcome.”

Kliegman said he’s also proud of his children and the education they received watching their father, their neighbors and the parade of experts who worked with Okanogan Highlands Alliance. Some of those experts became his daughter’s mentors. Sarah Kliegman is now working on her doctorate at the University of Minnesota, where she is studying how to clean up mine waste. Kliegman’s son, Joe, is a graduate student at the University of California, San Francisco, studying biophysics.

“It’s kind of how to turn lemons in to lemonade,” Kliegman said. “We stopped an open-pit mine. They were brought up believing you can get justice from the system.”

*greglamm@bizjournals.com | 206.876.5435*

Sunday, October 11, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment